The world was changing rapidly in the late 19th century. Railways crisscrossed continents, and factories hummed with the sounds of industrialization. Yet, transportation in cities and towns remained stubbornly tethered to horse-drawn carriages. In 1884, over 15.4 million draft horses were used to transport goods and people across America. That was until an inventive German engineer named Karl Benz introduced the world to a revolutionary idea: a self-propelled vehicle.

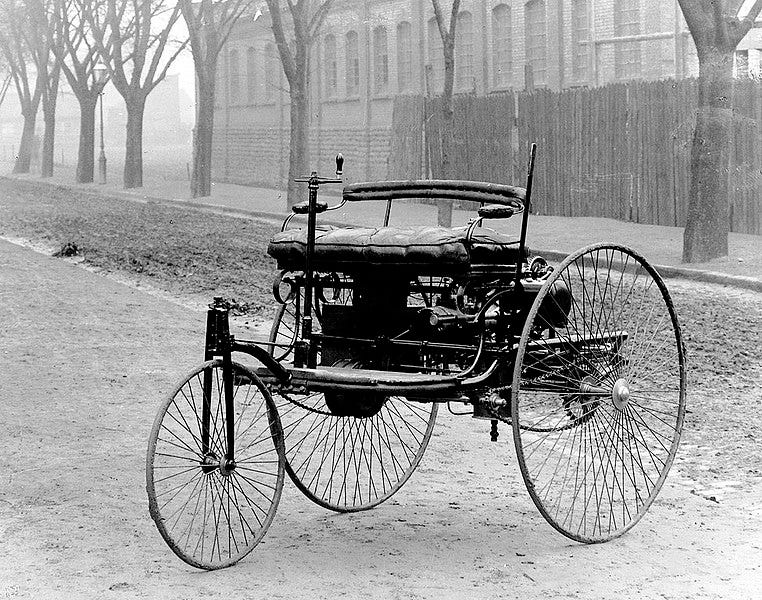

In 1886, Karl unveiled what is widely regarded as the first actual automobile: the Benz Patent-Motorwagen. The three-wheeled machine, powered by an internal combustion engine, looked nothing like the sleek cars we see today. Its spindly frame, wooden wheels, and single-cylinder gasoline engine producing less than one horsepower resembled a high-tech tricycle more than a modern vehicle. But it was groundbreaking—an invention that would change transportation.

At the time, Karl's creation was, to many, a mechanical curiosity. But it was a masterpiece of engineering. The heart of the Motorwagen was its internal combustion engine, an innovation refined by other inventors for use in industrial equipment, agricultural tools, and other areas. Karl took the concept and paired it with a lightweight chassis, pioneering the integration of engine and vehicle into a cohesive system. And with that, the car was born.

But inventing the first car was one thing; convincing the world to adopt it was another. Skepticism abounded. Critics dismissed the car as impractical, noisy, and even dangerous. Many doubted it could replace the reliability of horse-drawn carriages. Then came a pivotal moment, a breakthrough. But it didn't come from Karl. Rather, it resulted from a decision made by his wife, Bertha.

In 1888, Bertha took matters into her own hands. Literally. Without informing her husband, she took their two teenage sons and drove the car from home to her mother's house, a distance of about 66 miles. This was no small feat. Roads at the time were not designed for automobiles, and she encountered numerous challenges, from refueling at pharmacies (gasoline was sold as a cleaning solvent) to fixing mechanical issues with her hairpin and garter.

But it was worth it. Bertha's journey captured the public's imagination, proving that the automobile was more than an eccentric invention—it was a viable means of travel.

The Benz Patent-Motorwagen marked the dawn of an industry that would transform the world. Over the next few decades, inventors and entrepreneurs worldwide built upon Karl's foundation, making cars more affordable and accessible to the masses. Roads expanded, cities sprawled, and societies reorganized themselves around the freedom of mobility. By the mid-1890s, public perception began to shift, and demand for cars quickly outpaced supply.

One magazine captured this change: "Those who have taken the pains to search below the surface for the great tendencies of the age, know what a giant industry is struggling into being there. All signs point to the motor vehicle as the necessary sequence of methods of locomotion already established and approved. The growing needs of our civilization demand it; the public believe in it, and await with lively interest its practical application to the daily business of the world."

Today, it is estimated that 1.475 billion cars exist in the world.

Sources:

Flink, James J. “Three Stages of American Automobile Consciousness.” American Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 4, 1972, pp. 451–73. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2711684. Accessed 20 Nov. 2024.

“The Automobile Age.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-), vol. 10, no. 5, 1986, pp. 64–79. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40257092. Accessed 20 Nov. 2024.

Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Foundation, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1885Benz.jpg

Share this post