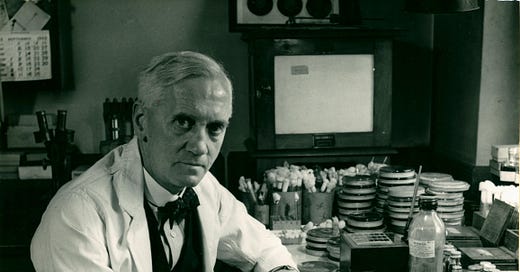

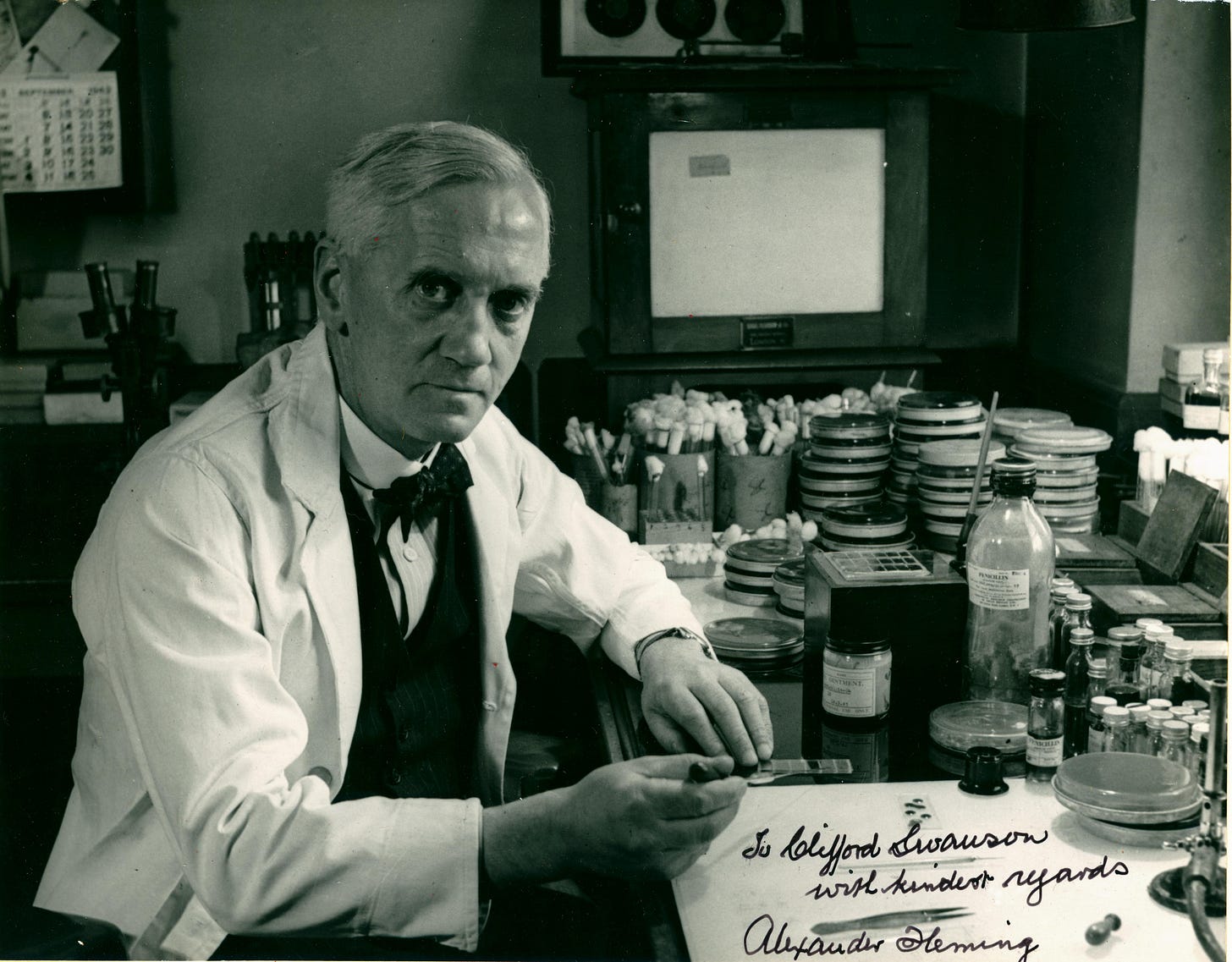

Sir Alexander Fleming returned to his bacteriology lab at St. Mary's Hospital in London after a two-week vacation on a warm September morning in 1928. Settling into his workspace, Alexander scanned the unattended Petri dishes. One in particular caught his eye. It sat uncovered next to an open window.

Alexander observed that a strange mold had taken root, its greenish tendrils spreading across the gel-like surface. But what struck him most was the clear area around the mold. He leaned in closer, his curiosity piqued.

It turned out that the mold, later identified as Penicillium, had contaminated the culture. Where the mold had grown, the bacteria had vanished. Something within the mold was killing the bacteria. What followed would change the course of medicine.

Realizing there might be significance to his discovery, Alexander set out to understand the mysterious substance at work. He conducted experiments to study the mold's properties. His notes detailed its remarkable ability to halt bacterial growth. Soon, he confirmed that it was not merely a coincidence but a potent natural antibiotic.

Yet, at the time, Alexander did not fully grasp the immense medical potential of penicillin, nor did he manage to refine it into a practical treatment. The challenge of isolating and mass-producing penicillin stalled progress for over a decade. It wasn't until the early 1940s when a team of researchers took up the task, that penicillin was successfully developed into the life-saving drug that would revolutionize modern medicine.

In recognition of their groundbreaking work, a couple of members from that research team, along with Alexander, jointly received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945.

Today, penicillin is considered one of history's most significant medical discoveries.

Amongst his many wisdoms, Alexander left us with the following,

"I have been trying to point out that in our lives chance may have an astonishing influence and, if I may offer advice to the young laboratory worker, it would be this—never neglect an extraordinary appearance or happening. It may be—usually is, in fact—a false alarm that leads to nothing, but may on the other hand be the clue provided by fate to lead you to some important advance."

Sources:

Birch, Beverley, and Fleming, Alexander. Alexander Fleming: Pioneer with Antibiotics. United States, Blackbirch Press, 2002.

Colebrook, L. “Alexander Fleming. 1881-1955.” Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, vol. 2, 1956, pp. 117–27. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/769479. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Navy Medicine, https://www.flickr.com/photos/navymedicine/36508522364/

Wikiquote (Lecture at Harvard University. Quoted in Joseph Sambrook, David W. Russell, Molecular Cloning (2001), Vol. 1, 153.), Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Alexander_Fleming

WOOLF, S. J. “SIR ALEXANDER FLEMING—MAN OF SCIENCE AND OF PENICILLIN.” American Scientist, vol. 33, no. 4, 1945, pp. 242–52. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27826081. Accessed 21 Feb. 2025.

Wild how much time it can take for a groundbreaking scientific discovery to evolve into applicable solutions to medical problems. Thanks for sharing!