"If nobody else is going to invent a dishwashing machine, I'll do it myself." - Josephine Cochrane

The plate was delicate, a soft white with blue floral edges, and so thin it seemed the sun could shine through it if you held it to the light. It had come from her mother and from her mother before that; a line of women passing beauty down like a family secret. But now, the plate was broken, lying in pieces on the kitchen counter.

Josephine Cochrane held the largest shard in her hand, her fingers tracing the jagged edges. Outside, the Illinois wind swept over Shelbyville, carrying the faint scent of smoke and damp earth. The world was moving forward as factories were rising and machines transforming lives. But here, in her kitchen, a simple plate had been undone by human hands. She thought about the seemingly endless chore of dishwashing.

And then, quietly, a thought settled in her mind.

Why not have a machine do it?

Josephine's world had always been full of movement. The grand dinners with their clinking glasses and swirling laughter, her husband William with his fine suits and big ideas, and the house bustling with servants and guests. But that world had gone quiet after William died in 1883, leaving her a widow with debts she didn't fully understand and a future she couldn't yet see.

Society didn't offer much sympathy for a woman in her position. People expected her to sell the house, dismiss the servants, and settle into some smaller, humbler life. But Josephine wasn't made that way. She was born in 1839, a child of Ohio's cold winters and wide, unbroken skies. Her grandfather built the first patented steamboat. There was something in her blood, something that couldn't let go of an idea once it took root.

And so, in the stillness of her new life, she began to tinker. She set up a small workshop behind the house, a cluttered room filled with sketches and tools she barely knew how to use. She had no formal mechanics training or grand education to fall back on. But what she did have was a fierce practicality and a sharp focus.

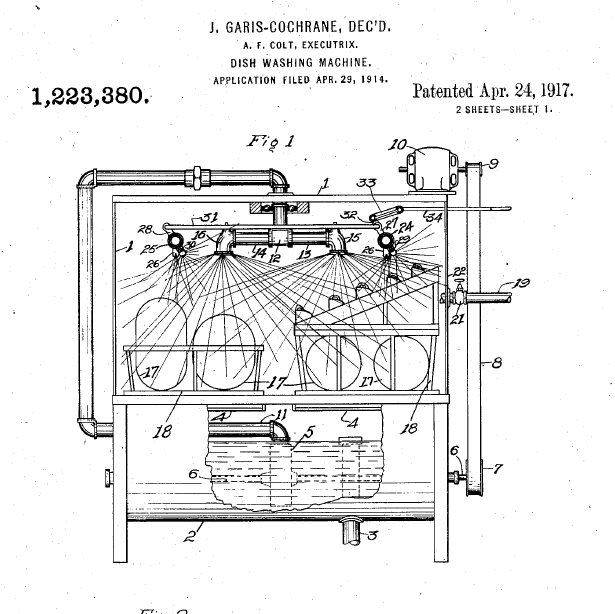

The first design was crude. Wire compartments shaped to hold plates and cups, all mounted on a wheel that could spin while jets of hot, soapy water sprayed over the dishes. It didn't look like much, but Josephine could see the beauty in its bones. She hired a mechanic to help refine her vision. Together, they worked through long days and cold nights.

By 1886, the machine was ready. Josephine turned the crank and watched as the wheel spun, water cascading over the plates. When the dishes came out clean without a single chip, she let out a quiet laugh or maybe a soft sigh. She'd done it. Two hundred dishes washed in just a couple of minutes.

Making a machine was only the first battle, however. Convincing the world it needed her invention would prove to be harder.

The men she pitched the dishwasher to were polite but dismissive. A machine for washing dishes? The men didn't care enough to invest. But Josephine had no patience for their condescension. She packed up her machine and began demonstrating it herself, which at the time took much courage. Josephine was almost fifty years old, but women of her class didn't often leave home without their husbands or fathers then. As she described one of her first sales pitches, "[it was] almost the hardest thing I ever did, I think, crossing the great lobby of the Sherman House alone. You cannot imagine what it was like in those days…for a woman to cross a hotel lobby alone. I had never been anywhere without my husband or father—the lobby seemed a mile wide. I thought I should faint at every step, but I didn't—and I got an $800 order as my reward."

She continued traveling to hotels, restaurants, and speaking to anyone else who would listen. And slowly, the orders began to trickle in. Her big break came at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The only woman presenting that year, her dishwasher stood among the gleaming inventions of the new age, and it won the highest award for "best mechanical construction, durability, and adaptation to its line of work."

Reflecting back on the work in later years, Josephine said, "If I knew all I know today when I began to put the dishwasher on the market, I never would have had the courage to start. But then, I would have missed a very wonderful experience."

Josephine wouldn't live to see her invention in every kitchen. She died in 1913. But her legacy lived on. Her company would eventually become KitchenAid, and her machine would find its way into homes worldwide.

Note: the beginning of this snapshot is based on real events, but was fictionalized.

Sources:

“I’ll do it myself.” United States Patent and Trademark Office, https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/journeys-innovation/historical-stories/ill-do-it-myself

Josephine Cochrane, Dishwashing Machine. Lemelson-MIT, https://lemelson.mit.edu/resources/josephine-cochrane

Share this post