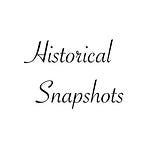

On a breezy morning in August 1926, nineteen-year-old Gertrude Ederle jumped into the cold waters of the English Channel. With her muscles relaxed from some rest after months of grueling training and her body coated head to toe in a mixture of lanolin, petroleum jelly, and grease for insulation against the chill and protection against the swarms of jellyfish, she felt determined and excited to attempt what no woman and only five men had ever done: swim across the Channel.

What followed would make Gertrude an international sensation.

Gertrude Caroline Ederle was born to German immigrant parents in New York City on October 23, 1905. The third of six children, she grew up in a lively household in Manhattan's Upper West Side, where during summer months, Gertrude's family would take outings to the New Jersey shore. It was on these sunny childhood days that a passion for swimming blossomed.

Soon, she turned the joy into a pursuit of competitive swimming, where success came quickly. Gertrude set her first world record at the age of 12. Between the ages of 15 and 19, she set 29 national and world records. In 1924, she represented the United States at the Paris Olympics, earning one gold medal in the 4x100-meter freestyle relay and two bronze medals in individual freestyle events.

Yet, she wanted to challenge herself more, to push her physical limits. And she also wanted to challenge the societal expectations placed on women. Which were many at the time.

Gertrude set her sights on swimming across the English Channel. Often referred to as the "Mount Everest of swimming" for its cold, rough waters teeming with jellyfish, the twenty-one-mile span was considered the ultimate test of endurance. Many believed that women were not physically capable of such a feat. Gertrude became determined to prove them wrong.

Her first attempt in 1925 ended in disappointment. Thinking she was in distress, her trainer touched Gertrude as he attempted to pull her from the water, disqualifying the swim. Though upset, Gertrude thought of her motto, if at first you don't succeed, try, try again. "I am going to attempt to swim the English Channel again next July," she said to herself.

For her second attempt, she hired a new coach and developed a rigorous training regimen, swimming four hours a day. She also designed a pair of goggles to better protect her eyes and a more aerodynamic swimsuit that minimized drag in the water.

On August 6, 1926, she started the swim at Gris-Nez, France with a tugboat carrying her coach and supporters trailing, offering encouragement and supplies of broth and sugar cubes for energy. She gave her team of supporters strict instructions about taking her out of the water: "until I get there or I can't move."

The swim was a battle from the start. Just a few minutes in, rough swells made her consider quitting. "But I thought I had to make a showing so I just kept on and on and on. When I got a few miles out I was confident I could make it and kept on," Gertrude later said.

Pushing through while singing her favorite song, Let Me Call You Sweetheart, she swam and swam. Even when her coach encouraged her to stop, Gertrude continued. "It's today or never, Pop," she shouted to her father and supporters on the tugboat. He replied, "Kiddie finish it."

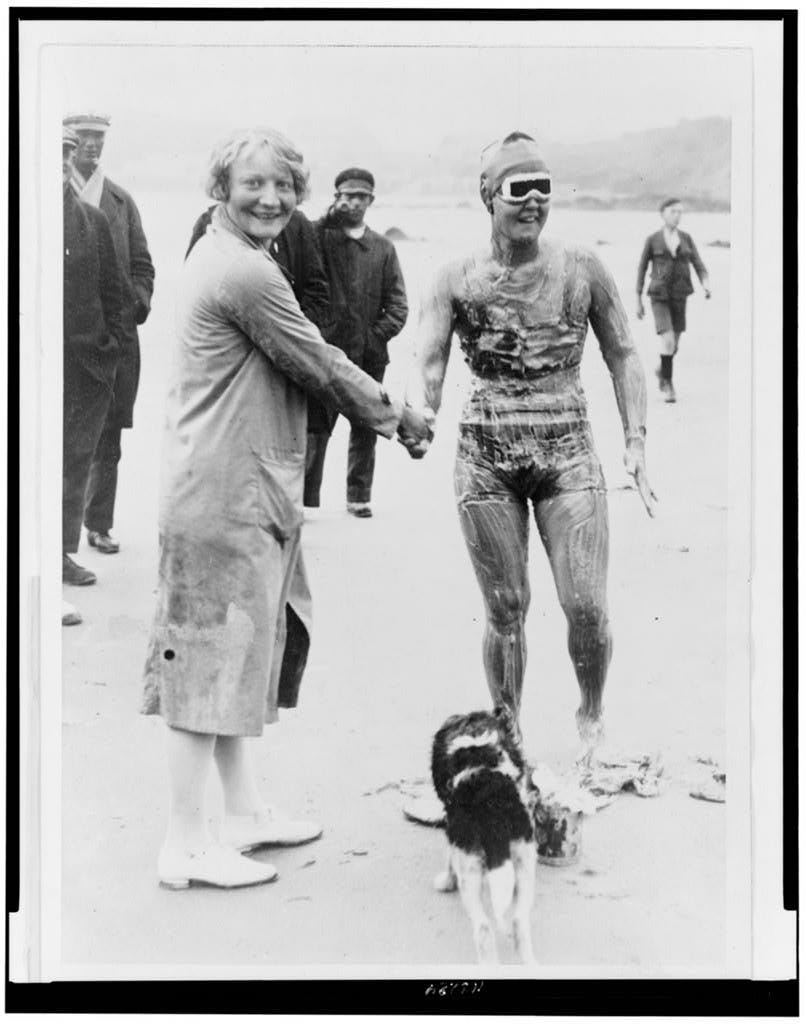

After 14 hours and 39 minutes, Gertrude emerged from the water onto the shores of Kingsdown, England. Her time was over two hours faster than the fastest man to have swum the Channel. Exhausted but triumphant, Gertrude became an international sensation. Newspapers worldwide hailed her achievement, and she was welcomed home to a ticker-tape parade in New York City attended by an estimated two million people. President Calvin Coolidge called her "America's Best Girl," a title she cherished throughout her life.

Gertrude soon retired and largely retreated from the public eye. She spent her later years teaching swimming to deaf children, a cause close to her heart as she herself became partially deaf after a childhood accident. On November 30, 2003, she passed away at the age of 98.

Sources:

Hasday, Judy L.. Extraordinary Women Athletes. United States, Children's Press, 2000.

“Life Story: Gertrude Ederle (1906–2003).” Women & The American Story, https://wams.nyhistory.org/confidence-and-crises/jazz-age/gertrude-ederle/

Lillian Cannon, of Baltimore, Md., offering her best wishes to Gertrude Ederle, as she starts out from Cape Griz Nez, France, on her successful attempt to swim the English Channel. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/95503395/>.

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.si.edu/object/gertrude-ederle%3Anpg_NPG.80.230

Parade for Gertrude Ederle coming up Broadway, New York City, with large crowd watching / photo by staff photographer. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/98510485/>.

“She was the First Woman to Swim Across the English Channel.” American Masters, PBS, https://www.pbs.org/video/she-was-first-woman-swim-across-english-channel-r8r7td/

St. Croix avis. (Christiansted, VI) 20 Aug. 1926, p. 3. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/sn84037526/1926-08-20/ed-1/.

The Milwaukee leader. (Milwaukee, WI) 8 Aug. 1926, p. 12. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/sn83045293/1926-08-08/ed-1/.

The Washington times. (Washington, DC) 7 Aug. 1926, p. 1. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/sn84026749/1926-08-07/ed-1/.

Share this post