Elsa Brändström didn’t set out to be a hero. She set out to help. But to the many soldiers she treated, she became one. The “Angel of Siberia” they called her.

Born in 1888 in St. Petersburg, Elsa was the daughter of the Swedish diplomat to Russia. Such an upbringing came with comfort, leisure, and elegance. Grand galas and fine dining. Life could have continued for her down the same path. Yet, Elsa chose something different.

When World War I broke out, she joined the Swedish Red Cross as a nurse. In 1915, she traveled to the Eastern Front, deep into Russia, to care for Austrian and German prisoners of war. The cold was brutal; people say your eyes can freeze if you don't blink enough in the long, harsh Siberian winter. But the camps were even worse.

For many, the trenches in Europe come to mind when thinking about the war. The Western Front. But it was on the vast stretch of land across Russia where millions of men were taken prisoner, and the highest number of soldiers died.

These men suffered from hunger and cold. Diseases spread fast. In Russian captivity, as many as one in four prisoners never came home. Elsa wrote,

The sick have but one wish, to stay among their comrades who are still unsmitten, where they have a little help and friendly words, and not to be sent to the isolation huts, where above and alongside of one dying men lie in delirium.

The overworked nurses have become blunted and give up the struggle. What help can they give when nothing is there, not even wood to prevent that daily painful freezing of the patients’ hands and feet.

If a man in his death agony falls from the topmost tier he lies on the stone floor until another knocks against him and pushes him aside. The body of the dead man is often the only prop of his still living neighbour, and days may pass before it is removed. Thus the stench of the living mingles with the odour of the dead.

She further wrote,

"The psychological effects of captivity made themselves more and more felt. A gnawing unrest, a despairing feeling of emptiness, of disgust at everything spreads everywhere. Like an evil spirit these feelings take possession of the prisoner, yielding only for a time to physical pain. They drive him out of the huts—to walk, anything to walk, on and on, round and round, now forming this figure, now that—anything to bring that weariness which leads to the longed-for, dreamless sleep. He seeks out comrades whose company he formerly found pleasant and stimulating, but his own irritability, like theirs, makes intercourse intolerable. Men formerly the best of friends can now scarcely bear the sight of one another, and a mere trifle, which otherwise would pass unnoticed, may now lead to blows. Everything gets on one’s nerves. One is critical; one is annoyed because this man laughs, the other coughs, the third snores, the fourth talks too much and the fifth never speaks at all."

Elsa gave these men all her care. She tended to them, bringing some ease and comfort, and kept many alive who would have likely died otherwise.

War's end didn't stop the bloodshed in Russia. The Revolution and Civil War followed. Erupted may be the more apt term. Communists overthrew the monarchy, as millions of people died in the upheaval. Many fled to escape the violence.

Elsa stayed, but was soon arrested on suspicion of espionage. She was held for weeks or possibly even months, stripped of her papers, and questioned often. Though the Soviet authorities never found evidence against her, they saw her foreign status and movements through war-torn zones as suspicious. Ultimately, it was diplomatic pressure from Sweden and her affiliation with the Swedish Red Cross that led to her release. But Russia expelled Elsa and she was never allowed to return.

After the war, Elsa moved to Germany and Austria, lands now devastated by famine, inflation, and despair. Cities lay in ruins, fathers gone, and mothers begging in the streets. Elsa focused on the most vulnerable: the children. She helped build homes for orphans and organized training schools, giving young people skills to support themselves.

But peace didn’t last long. As the Nazis rose to power, Elsa’s humanitarian work and her international connections made her presence in Germany increasingly difficult. With war on the horizon, she and her husband left for the United States, settling in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she continued devoting herself to helping refugee children, war widows, and displaced families across Europe.

Elsa would reflect back on her experiences and say,

“It is up to us women to heel (sic) what the war has broken, to mother the suffering and to help them to get back to their belief in humanity. We must give the victims of the war back their desire to live and to become again useful human beings.”

Elsa passed away in 1948.

Sources:

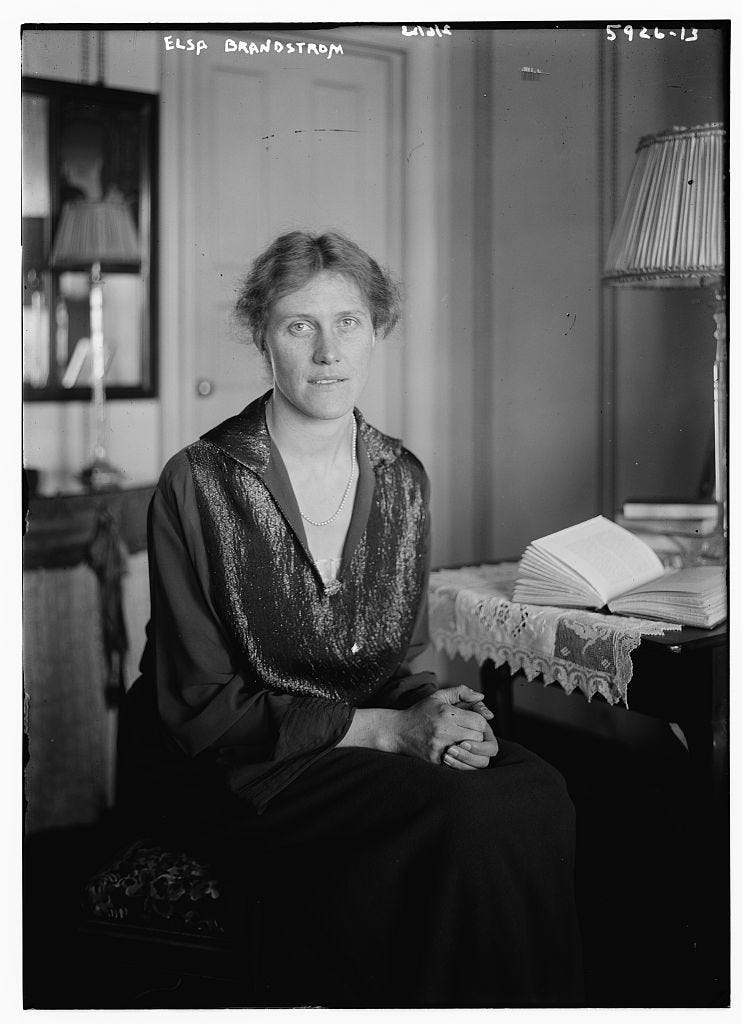

Bain News Service, Publisher. Elsa Brandstrom. [Between and Ca. 1925] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2014715690/>.

Brändström, Elsa. Among Prisoners of War in Russia and Siberia. Translated by Pauline de Chary, Macmillan, 1929.

Davis, Gerald H. “National Red Cross Societies and Prisoners of War in Russia, 1914-18.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 28, no. 1, 1993, pp. 31–52. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/260800. Accessed 9 May 2025.

Durand, André. “Elsa Brändström (1888–1948).” International Review of the Red Cross, vol. 30, no. 276, Aug. 1990, pp. 355–365. International Committee of the Red Cross, https://international-review.icrc.org/sites/default/files/S0020860400011396a.pdf.

“Elsa Brändström.” Women in Peace, 21 Aug. 2019, https://www.womeninpeace.org/b-names/2019/8/21/elsa-brndstrm.

Grant, Susan. “War and Revolution.” Soviet Nightingales: Care under Communism, Cornell University Press, 2022, pp. 17–34. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctv310vkht.7. Accessed 9 May 2025.

An absolutely beautiful story about a time of pure horror.

Thank you for this one!