Ellen Swallow Richards achieved many firsts for American women in education and science. More importantly, her pioneering work in environmental science and home economics helped lay foundational principles that advanced these fields and elevated public health and household management standards.

Ellen was born on December 3, 1842, in the small, rural town of Dunstable, Massachusetts, where she was raised on the family farm. Her parents, both educated teachers, decided to homeschool their daughter, nurturing an appreciation for learning and kindling an initial love for science. At the age of sixteen, Ellen's formal education began in earnest when her family moved to Westford, Massachusetts, where she attended Westford Academy.

While advanced education for women was rare then, Ellen's academic abilities and dedication led her to pursue a college degree. After several years of teaching, Ellen was accepted into Vassar College, a groundbreaking institution in its own right, for advancing women's education and combating the belief some had that women's "nervous systems will not adapt to higher learning." Though the college was cautious in its early years. In a letter from the time, Ellen writes to her mother, "The only trouble here is they won't let us study enough. They are so afraid we shall break down, and you know the reputation of the college is at stake, for the question is, can girls get a college degree without injuring their health."

But here at Vassar, her passion for science deepened. Supported by faculty who believed in women becoming scientists, Ellen's career aspirations took shape as she chose to focus on chemistry because of the field's practical applications to life.

Upon graduating, Ellen faced another formidable challenge: finding work. Unable to do so, one of her potential employers recommended that she apply to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). This too was a challenge. MIT had never accepted a female student. In 1871, Ellen became the first one. Though her admission was as a "special student," a status reflecting the fact that women were not yet formally admitted to degree programs.

At MIT, Ellen began conducting research under a professor who was against the idea of a woman attending the university. Yet, he gave her full responsibility to conduct research for a government project on water sewage in Massachusetts. And when it came time for him to present the findings, he gave Ellen credit for her hard work, saying, "Most of the analytical work has been performed by Miss Ellen Swallow... I take pleasure in acknowledging my indebtedness to her valuable assistance by expressing my confidence in the accuracy of the results obtained."

Ellen's work at the university quickly earned her a reputation as one of the foremost water scientists in the U.S. And despite the challenges of being a female student in a male-dominated institution, Ellen wrote humbly to a friend,

"I hope that I am winning a way which others will keep open. Perhaps the fact that I am not a radical, and that I do not scorn womanly duties, but deem it a privilege to clean up and supervise the room and sew things, etc., is winning me stronger allies than anything else… I am useful in a general way, and they can't say study spoils me for anything else."

Ellen's contributions to environmental science were groundbreaking and far-reaching. She conducted extensive research on water quality, which led to significant advancements in sanitation and public health, and her other pioneering research and advocacy were instrumental in shaping standards during a time when waterborne diseases were rampant.

In addition, Ellen's influence extended into the home, where she sought to apply scientific principles to everyday household management. Following her philosophy that "the quality of life depends on the ability of society to teach its members how to live in harmony with their environment—defined first as the family, then with the community, then with the world and its resources," she emphasized the importance of clean water, proper sanitation, and efficient household management as critical components of a healthy and productive life. This approach revolutionized Americans' views of home economics, transforming it from mundane tasks into a science-based discipline with far-reaching implications for family health and societal well-being.

Throughout her career, Ellen taught at MIT for about 40 years. During that time, she authored over 15 books and many articles.

As for Ellen the person, a friend described her by saying, "she was a woman of a few words, but she had a transfiguring touch; and her rare intellectual quality—her power of dropping a few words and transporting you to a larger world—was supplemented by a personality which commanded affection and allegiance in a remarkable degree."

Ellen passed away in 1911.

Sources:

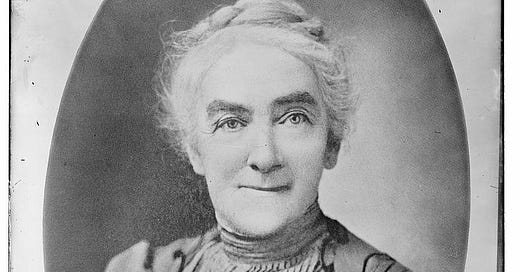

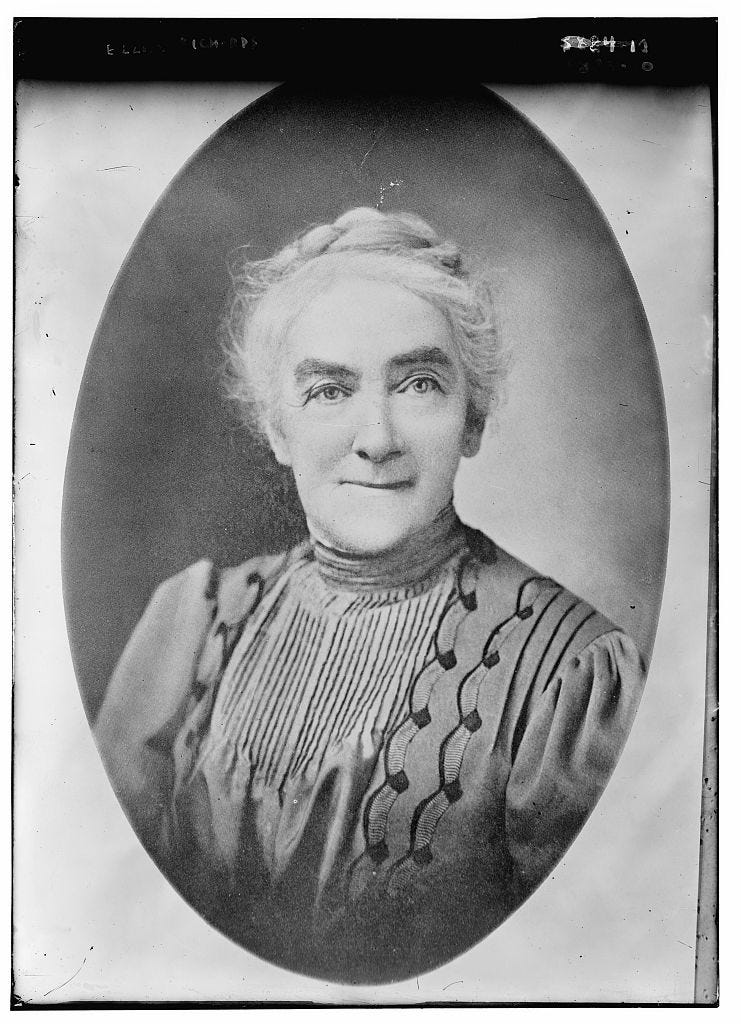

Bain News Service, Publisher. Ellen Richards. [Between and Ca. 1920] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2014702017/>.

Dyball, Robert, and Liesel Carlsson. “Ellen Swallow Richards: Mother of Human Ecology?” Human Ecology Review, vol. 23, no. 2, 2017, pp. 17–28. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26367977. Accessed 9 Aug. 2024.

“Ellen Swallow Richards ’1870.” Vassar Encyclopedia, https://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/distinguished-alumni/ellen-swallow-richards/

Zach, Kim K.. Hidden from History: The Lives of Eight American Women Scientists. United States, Avisson Press, 2002.