It was March 1936, and the U.S. was in the throes of a struggle that seemed never-ending. The Great Depression was ravaging the land, and in the Midwest, dust storms were also sweeping across the plains, forcing tens of thousands from their homes and driving them to seek refuge where they could. Some piled their few belongings into rusted-out cars and battered pickup trucks, others took to the trains, and some just wandered along the highways with their thumbs up, looking for a ride, all drifting westward in a desperate search for anything to grow or earn money to buy food. They knew nothing but the soil, so they came, thinking of California's fertile fields.

When they arrived in California, the reality was harsher than the dreams they'd clung to. They moved from one county to the next, chasing the harvests like migrating birds but finding only meager pay for back-breaking work picking various fruit and cotton. Their homes were makeshift, nothing more than ragged tents, cardboard shacks, and scraps of tin that barely kept the elements at bay. They washed themselves in the same stagnant ditches where they drew their water. It was a life of little more than survival.

It was amidst this relentless despair that Dorothea Lange had worked for the past month as a government photojournalist, traveling across different migrant camps and taking photographs of the people. She worked their hours, sixteen a day.

Now, she gripped the steering wheel as the rain drummed relentlessly on the windshield as she drove home, worn out and tired. Then, she noticed a sign for a pea pickers camp.

She drove past the camp at first. But Dorothea, who believed in following her intuition, felt something compelling. After debating for nearly 20 miles, she turned around and drove back. “I was following instinct, not reason; I drove into that wet and soggy camp and parked my car like a homing pigeon,” Dorothea later said.

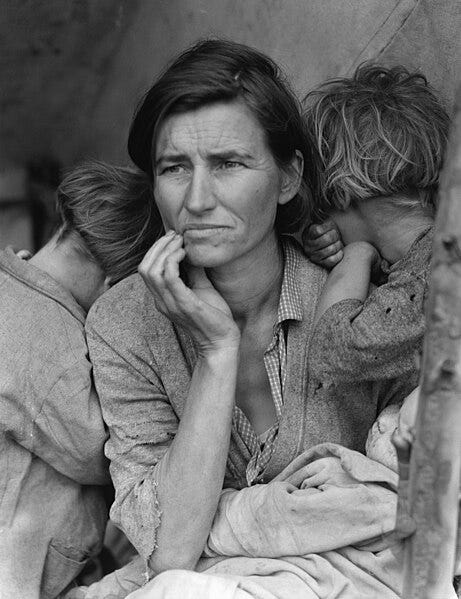

At the camp, Dorothea met thirty-two-year-old Florence Owens Thompson, a migrant worker and mother of seven children. As Dorothea described years later,

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions…She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean- to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

Then Dorothea did what she knew best and began taking photographs of Florence with the children. One image in particular, depicting Florence with several of her children huddled around her, became one of the most enduring images of the Great Depression, symbolizing the plight of struggling families during that era. That photograph became known as "Migrant Mother."

Note: click here for part II.

Sources:

“Dorothea Lange's ‘Migrant Mother’ Photographs in the Farm Security Administration Collection.” Library of Congress, https://guides.loc.gov/migrant-mother

“Dorothea Lange + Migrant Mother.” The Kennedy Center, https://www.kennedy-center.org/education/resources-for-educators/classroom-resources/media-and-interactives/media/media-arts/dorothea-lange-migrant--mother

Lange, Dorothea, and Cox, Christopher. Dorothea Lange: Aperture Masters of Photography Number Five. United States, Aperture, 1987.

Lange's "The Assignment I'll Never Forget: Migrant Mother," Popular Photography, Feb. 1960

Partridge, Elizabeth. Restless Spirit the Life and Work of Dorothea Lange. N.p., Perma-Bound Books, 1998.

Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lange-MigrantMother02.jpg

She saw life in a different way.

I enjoy reading the story.

Thanks for sharing the story behind this iconic image.