Beatrix Farrand, born in 1872 in New York City, grew up with the benefits of life in a family of means. In particular, her mother and aunt, the renowned writer Edith Wharton, exposed a young Beatrix to a world of art, culture, and intellectual pursuits from a young age. They, along with other family members, also supported Beatrix's developing interest in landscapes and gardens, which followed a family lineage of loving gardens. As her uncle, who had become somewhat of a surrogate father to Beatrix after her parents divorced, said, "Let her be a gardner or, for that matter, anything she wants to be. What she wishes to do will be done well."

The path to becoming a landscape architect would be challenging. The profession was overwhelmingly male-dominated at the time, and women were often excluded from public projects. And no schools offered the specialized training she required. Yet, despite both challenges, Beatrix felt determined to pursue her passion.

It did help, of course, that her family's status and connections could provide Beatrix with valuable opportunities, including an introduction to Charles Sprague Sargent, the director of the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard University. Charles became one of Beatrix's first mentors, teaching her the importance of respecting nature's order. This principle—that landscape architecture should harmonize with nature rather than impose upon it—became the foundation of Beatrix's design philosophy, distinguishing her from many of her contemporaries who favored more imposing designs.

In 1895, Beatrix took a bold step by opening her own landscape architecture firm, making her one of the first women in the United States to do so. In just her mid-20s still, Beatrix quickly gained a reputation for conducting projects such as private gardens and estates with meticulous care and sensitivity to the natural environment. We can glean some insight into her work process from a note she wrote to one client, the Rockefellers, as she worked on a garden for them,

"Perhaps I have spent more time than was necessary in 'mulling' over things, letting the feeling and character of the whole place become a subconscious part of my mind. As you and Mrs. Rockefeller both know, the garden has not been an easy one to design, and if you finally think it successful it will be the result not only of my work but of your own in your constant helpfulness and willingness to discuss its various aspects."

Beatrix was diligent, working often, even on her many train rides to and from projects. As described by an employee at her company,

"I would bring the drawings being developed at the office and get on the train in New York and meet her on the train. She was usually on her way to do fieldwork in one of the jobs. We would review the plans, she would make suggestions and critiques or changes. As soon as the review was finished, I would get off at the next station, wherever that may be, and take a train back to New York."

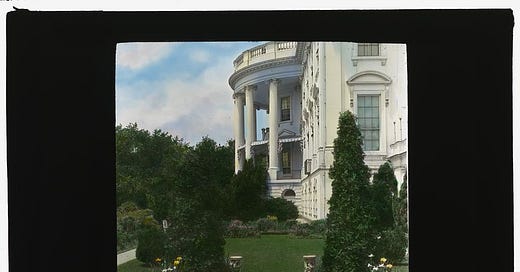

Despite the many slights and obstacles Beatrix faced as a woman in the field, as her reputation grew, so did the scale and scope of her projects. She would earn some of the most prestigious commissions of her time, including some of the gardens at the White House, Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C., and the campus of Princeton University.

Alongside her design work, one of Beatrix's most notable achievements was her involvement in founding the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) in 1899. As the only female founding member, she played a crucial role in establishing the organization that would set professional standards for the field and shape the future of landscape architecture.

Throughout her career, Beatrix's dedication to harmonizing human design with the natural world left an indelible mark on landscape architecture. Her gardens continue to inspire and delight, embodying a timeless balance between art and nature.

Beatrix passed away in 1959.

Note: check out latest snapshot book, a biography of Frederick Douglass on Kindle.

Sources:

Balmori, Diana, et al. Beatrix Farrand's American Landscapes: Her Gardens and Campuses. United States, Timber Press, Incorporated, 1985.

"Beatrix Jones Farrand cabinet card est 1890s-1910s." Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Foundation, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beatrix_Jones_Farrand_cabinet_card_est_1890s-1910s.jpg

Beatrix Jones Farrand (1872-1959): Fifty Years of American Landscape Architecture. United States, Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, 1982.

Johnston, Frances Benjamin, photographer. White House,Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C. Southeast garden. [Spring] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2007685051/>.

PEARSON, CARMEN. “Introducing the Life and Work of Beatrix Farrand, Landscape Gardener and Writer (1872–1959).” Legacy, vol. 25, no. 1, 2008, pp. 128–141. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25679635. Accessed 12 Aug. 2024.

Very interesting. I had never heard of her. Having had Edith Wharton as an aunt must have been something!

Dumbarton Oaks is still one of the most beautiful gardens